The fern is a modest sort. It creeps below the forest floor, surfacing now and then to unfurl its foliage. It eschews heavy perfume and bright flower, opting instead for basic green. Indeed, I always thought of the fern as ordinary. It wasn’t until I crouched down to study the fern’s fretwork foliage, its ancient history, and its odd habits that I came to see it as anything but.

The fern maintains its own lingo. While other plants make do with stem, leaf, and shoot, the fern prefers rhizome, frond, and crosier. No unseemly pollination for the dignified fern. It procreates via “alternation of generations,” sending its dustlike spore wafting on air; upon landing, the spore grows into a tiny plant called a prothallus, which produces the familiar fern. “It would be as if our eggs and sperm produced little beings, ten inches tall, and they had sex and we didn’t,” says Warren Hauk, associate professor of biology at Denison University in Granville, Ohio, and past president of the American Fern Society.

The fern has clung to Earth for 350 million years. Today Pteridophyta, the fern phylum, comprises some 12,000 species and thrives in landscapes from the equator to the northern boreal forests. The mosquito fern, a mere speck, grows dense across lakes. The frilly wood fern pads the forest floor. The climbing fern rappels brick walls. The moonwort unfurls a single scalloped leaf each year, dotting sand dunes and mountainsides. In spring, the Himalayan maidenhair fern glistens salmon pink. In autumn, the royal fern glows golden orange.

Fern Vocabulary:

SPORES

Ferns do not have flowers or seeds; they instead reproduce sexually by spores. The undersides of fertile fronds are decorated with patterns of sori, clusters of up to 100 spore cases that each enclose 64 spores. When ripe, the cases open, releasing millions of tiny spores.

CROZIER

It is the graceful unfurling of the fiddleheads in spring that first calls our attention to ferns. Unlike the leaves of most plants, which grow in all directions, the fern frond matures from the base up — the crozier’s tight spiral uncoils into the leaf’s characteristic blade shape.

RHIZOME

Neither nature nor the gardener has to depend solely on spores for reproduction. In most fern species, vegetative propagation occurs through the branching of the plant’s underground portion, or rhizome. On the lower side of the creeping rhizome are slender roots that provide stability and take in nourishment for the plant. New fronds are produced at the branch tips.

After disaster strikes—lava flow, say, or forest fire—the fern is often the first to take root. In 2006 the Washington Post reported on a colony of maidenhair ferns thriving in a D.C. Metro station, some 150 feet underground. “They’re survivors,” says Michelle Bundy, curator of the Hardy Fern Foundation in Federal Way, Washington. “They’re tough.”

As well as tender. In the storybook, the fern hosts fairies. In medicine, it eases aches. In the decorative arts, it’s shorthand for tasteful. That’s why the Victorians developed a mass case of “pteridomania,” fern fever. The image of the fern was pressed into pottery, stitched onto pillows, and cast into ironwork. The fashionable Victorian sitting room was graced by a Wardian case—an early terrarium—overflowing with ferns. A formal fern conservatory, called a fernery, was thought an appropriate addition to Victorian parks, concert halls, and mental hospitals. “It showed you had good taste because you saw the appeal of foliage plants rather than gaudy, garish flowers,” says Sarah Whittingham, author of The Victorian Fern Craze (Shire, 2009). (For more on the Victorians’ passion for ferns “The New Victorians”)

“The Victorian fern craze never stopped,” saysSerge Zimberoff, owner of Santa Rosa Tropicals, a nursery in Santa Rosa, California. In high season the company ships 100,000 “clone grown” ferns from laboratory to nursery each week. “Look on TV,” Zimberoff says. “Whenever a person is speaking, there’s always a big Boston fern nearby.”

By the 1960s, the potted fern had moved into the dorm room and living room, where it was tended by a guy with a copper misting can and a girl, likely as not, named Fern. It got suave in the 1970s, when no singles-bar pickup line could be smoothly delivered without a fern overhead.

Today gardeners appreciate the low-maintenance, high-style fern more than ever, and landscapers are keen on the indelicately named stumpery, where ferns frolic among logs. Prince Charles keeps a stumpery. “Ferns have a really neat perspective on life,” says Tom Goforth, owner of Crow Dog Native Ferns and Gardens in Pickens, South Carolina. “They developed this lifestyle a way long time ago. Ferns, I think, just decided, ‘Man, we’ve got this all worked out. Why change?’?”

Our Favorite Ferns

Photo by: Bryan Whitney.

Japanese Tassel Fern (Polystichum polyblepharum)

Zones 4–9. Shade. This lacy evergreen reaches a height of 24 to 32 inches.

Photo by: Bryan Whitney.

Cabbage Palm Fern (Phlebodium aureum)

Zones 8–10. Sun to full shade. A tropical fern, it has creeping rhizomes that make it an eye-catching choice for a hanging pot.

Photo by: Bryan Whitney.

Staghorn Fern (Platycerium)

Zones 10–11. Sun to partial shade. It’s treasured for its long, graphic, graceful fronds.

Photo by: Bryan Whitney.

Rabbit’s Foot Fern (Davallia fejeensis)

Zones 10–11. Light to full shade. Named for its furry rhizomes, it looks great in an urn or a hanging basket.

Photo by: Bryan Whitney.

Lemon Button Fern (Nephrolepis cordifolia)

Zones 8–10. Partial shade. This fern’s fronds are composed of small, round leaflets. It grows to just about a foot.

Photo by: Bryan Whitney.

Victoria Lady Fern (Athyrium filix-femina ‘Victoriae’)

Zones 4–8. Partial to full shade. This deciduous fern was a favorite during the Victorian era. And it’s deer resistant.

Photo by: Bryan Whitney.

Japanese Holly Fern (Cyrtomium falcatum)

Zones 8–11. Partial to full shade. A tropical fern with glossy, dark, holly-shaped fronds, it makes a fetching, low-maintenance houseplant.

Photo by: Bryan Whitney.

Bird’s Nest Fern (Asplenium nidus)

Zones 10–11. Light shade. This fern, with glassy, bright fronds, loves humidity.

Photo by: Brenda Weaver.

Australian Tree Fern (Cyathea cooperi)

Zones 8–11. Sun to partial shade. The coiled fiddlehead unfurls as the tree fern matures.

Indoor Fern Care Tips

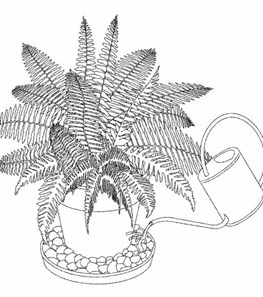

Photo by: Brenda Weaver.

Moisture

Water ferns only when the top of the soil is slightly dry. To maintain moisture, fill a saucer with pebbles, place the potted fern on the pebbles, and put a small amount of water in the saucer.

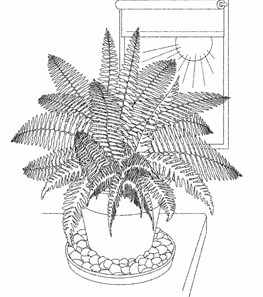

Photo by: Brenda Weaver.

Light

Ferns generally prefer indirect light; too much direct sunlight will burn their fronds. Adjust your window blinds to create the right light, or move the fern away from the window.

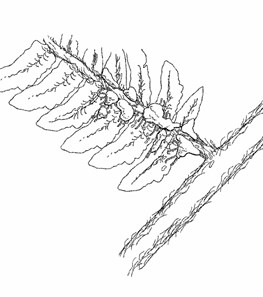

Photo by: Brenda Weaver.

Pests

If insects such as whiteflies or aphids appear, wash the fronds gently with water or spray them with a natural indoor-plant insecticide, diluted to half strength.